Call it the case of the missing moon. Scientists using data obtained by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft and computer simulations said on Thursday the destruction of a large moon that strayed too close to Saturn would account both for the birth of the gas giant planet’s magnificent rings and its unusual orbital tilt of about 27 degrees.

The researchers named this hypothesized moon Chrysalis and said it may have been torn apart by tidal forces from Saturn’s gravitational pull perhaps 160 million years ago – relatively recent compared to the date of the planet’s formation more than 4.5 billion years ago.

About 99% of the Chrysalis wreckage appears to have plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere while the remaining 1% stayed in orbit around the planet and eventually formed the large ring system that is one of the wonders of our solar system, the researchers said. They chose the name Chrysalis for the moon because it refers to a butterfly’s pupal stage before it transforms into its glorious adult form.

“As a butterfly emerges from a chrysalis, the rings of Saturn emerged from the primordial satellite Chrysalis,” said Jack Wisdom, a professor of planetary science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and lead author of the study published in the journal Science.

The researchers estimated that Chrysalis was roughly the size of Iapetus, Saturn’s third-largest moon that has a diameter of a little over 910 miles (1,470 km).

“We assume it was mostly composed of water ice,” said planetary scientist and study co-author Burkhard Militzer of the University of California, Berkeley.

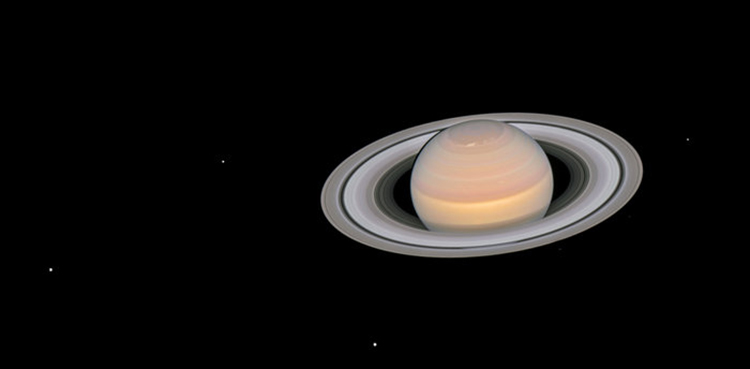

Saturn’s rings, predominantly made of particles of water ice ranging from smaller than a grain of sand up to the size of a mountain, extend up to 175,000 miles (282,000 km) from the planet but generally are only about 30 feet (10 meters) thick. While the solar system’s other large gas planets including Jupiter also possess rings, they are paltry compared to those of Saturn, the sixth planet from the sun.

Located nearly 10 times as far from the sun as Earth, Saturn is the second-largest planet in our solar system behind Jupiter, with a volume 750 times greater than Earth. Saturn, made up mostly of hydrogen and helium, is orbited by 83 known moons, including Titan, the solar system’s second-largest moon – bigger than the planet Mercury.

Cassini orbited Saturn 294 times from 2004 to 2017, obtaining vital data including gravity measurements that were key to the new study, before the robotic explorer made a death plunge into the planet.

A study published in 2019 provided evidence that the rings were a relatively recent addition, and the new research expanded on those findings. In the new study, the researchers proposed a multi-step process to explain the formation of Saturn’s rings.

The Saturnian system formed with Chrysalis among the many moons present, they said. At the outset, the planet’s spin axis was perpendicular to its orbital plane around the sun but the gravitational effects of the distant planet Neptune on the Saturnian system tilted Saturn’s spin axis.

The drama began when Titan’s orbit around Saturn began to drift outward – a process still occurring – destabilizing the orbit of Chrysalis, they said. Titan’s outward migration is considered relatively rapid, at about 4 inches (11 cm) per year – which does not sound like much but over time amounts to a lot, especially for such a big moon.

The orbit of Chrysalis deteriorated and the moon ventured so close to Saturn that it disintegrated, the researchers said.

“Saturn’s gravitational force ripped it apart in the way Jupiter ripped apart the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet,” Militzer said, referring to a comet that ultimately plummeted into Jupiter in 1994.

“With Chrysalis gone, Neptune no longer could change Saturn’s spin axis. So the planet was left spinning at an angle of 27 degrees,” Militzer added.

Also Read: WATCH: The ‘great conjunction’ of Jupiter and Saturn

In comparison, Earth’s tilt is about 23 degrees.

from Science and Technology News - Latest science and technology news https://ift.tt/AFs7wUn